By The Editorial Board

It is 2025, yet the same recycled political actors are already crawling out of the shadows, brandishing their old titles as Vice Presidents, Governors, and Senators as supposed qualifications for the 2027 presidency. Once again, Nigerians are being asked to mistake mere political titles for proven leadership.

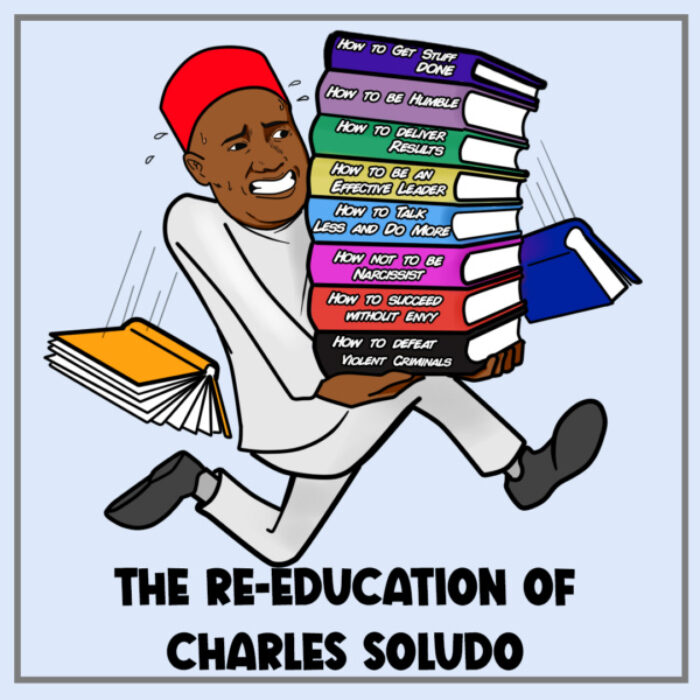

It is therefore time to dismantle one of the most dangerous fictions in Nigerian politics: the belief that holding the office of Vice President, Governor, or Senator somehow qualifies a person to become President.

This lie has crippled the nation for decades. It assumes that proximity to power is the same as capacity for leadership. It is not. Titles are not qualifications. Experience in mediocrity does not prepare anyone for the burdens of real leadership.

Take the role of Vice President. In Nigeria, it is not a leadership position. It is a lesson in irrelevance. The Vice President is often a political accessory — sidelined, neutered, and reduced to symbolic appearances. He does not command the military. He does not shape fiscal or monetary policy. He does not control national security. In most administrations, he is a figurehead at best and a scapegoat at worst. The position teaches survival, not statecraft.

The same can be said for most Governors, though not all. There are a few truly exceptional governors whose leadership and vision could translate well to the presidency. We will profile these few governors in a future editorial.

However, many others who present themselves as qualified for national office are little more than glorified treasurers — managers of federal handouts rather than true leaders.

Their primary role has been to collect monthly allocations from Abuja, distribute the money among loyalists, and oversee a system of consumption without real governance or development.

Each month, they collect allocations from Abuja, distribute the funds among party loyalists, contractors, and sycophants, and squander the rest on bloated administrative salaries.

Often, they cannot even meet the barest duties of leadership: paying teachers, funding hospitals, maintaining roads, securing farmers and schoolchildren, or providing clean drinking water. They do not build economies, reform education, or attract investment.

Many cannot even run their overstaffed government houses without begging for constant federal bailouts. What they call governance is consumption without production, waste without innovation, and corruption without shame. They are caretakers of decay, presiding over underdevelopment.

Their so-called achievements are usually cosmetic, wasteful white-elephant projects designed to deceive the gullible and feed hollow social media propaganda.

The National Assembly is no better. It is a graveyard of ideas, a sanctuary for retired governors and recycled politicians. Senators do not legislate national progress. They legislate personal enrichment. Most do not sponsor meaningful bills. Few have any grasp of national policy. They obsess over contracts, allowances, and power games. They legislate in silence and retreat in luxury while the country burns.

None of these positions, Vice President, Governor, or Senator, inherently prepares anyone for the weight and complexity of the Nigerian presidency. The presidency is not a reward for loyalty or longevity. It is a sacred responsibility, requiring vision, courage, intelligence, and discipline. It requires the capacity to confront entrenched systems, lead in crisis, and rebuild a failing state. These roles, as they currently function, do not demand any of those qualities.

The Case Files

Atiku Abubakar served as Vice President under President Obasanjo for eight years, tasked with leading Nigeria’s economic reforms, particularly the privatization of public enterprises. What should have been a chance to restructure the economy became one of the most blatant episodes of elite enrichment in Nigeria’s democratic history.

Instead of driving innovation or building national institutions, Atiku oversaw a deeply flawed and opaque privatization process that handed public assets to cronies, political allies, and shell companies lacking competence.

Key industries were gutted, public monopolies were replaced by private cartels, and major sectors, from power to steel, collapsed under the guise of reform. No jobs were created. No sustainable growth followed. Public trust eroded as collective wealth was auctioned off in secretive deals. Atiku entrenched political influence but delivered no national development, no enduring institutions, and no economic strategy.

Yet he still touts this record as proof of readiness to lead. It is not. What Nigeria needs is not another architect of backroom deals, but a builder of systems. Atiku’s legacy shows he is the former — never the latter.

Goodluck Jonathan is perhaps the most literal example of a Vice President who stumbled into the presidency unprepared — and proved, in real time, that the position does not equip anyone to lead a complex nation. Elevated by political accident rather than performance, Jonathan moved from Deputy Governor to Governor, then to Vice President, and finally to President following the death of Umaru Musa Yar’Adua.

At every step, he was carried by circumstance, not competence. His presidency was marked by paralysis, confusion, and an inability to confront the crises of corruption, terrorism, and institutional decay. Under his watch, the Boko Haram insurgency exploded unchecked. Billions vanished in oil theft and subsidy scams.

The NNPC was a black hole of missing funds. Rather than assert leadership, Jonathan’s presidency was defined by indecision and the perception that he was not in control. His time in office stands as a warning: ascending through titles is not the same as rising through merit. His failure was not just personal — it was structural, and it exposed how unprepared most of Nigeria’s political elite truly are.

Bola Ahmed Tinubu is the most damning proof that governorship does not prepare one for the presidency. Once hailed as the architect of modern Lagos, he came to the presidency with more political machinery than any of his peers. Yet less than two years into office, Nigeria is in crisis. Inflation is out of control, the naira is in freefall, food and fuel prices have skyrocketed, and insecurity has worsened.

His cabinet is bloated with recycled loyalists, not technocrats. Despite decades to prepare, he arrived without a plan, without a competent team, and without the energy or clarity to lead. If Tinubu, with all his political capital, could fail this catastrophically, what more proof is needed that being a governor is no qualification at all?

Peter Obi, often praised for fiscal prudence, also exemplifies the limits of governorship. As governor of Anambra, he emphasized saving money but failed to tackle the state’s deeper structural problems. Deindustrialization worsened. Job opportunities collapsed. Insecurity spread. Health and education systems decayed. Corruption thrived. Infrastructure was neglected.

Savings without transformation is not leadership. Nigeria does not need a bookkeeper. It needs a nation builder with the ability to allocate capital and human resources to drive economic growth, social development, and public safety.

Therefore, his bureaucratic experience as Anambra State governor is a cautionary tale of how mere financial conservatism, absent bold investment and structural reform, entrenches underdevelopment. His limited, incomplete record in a small state, while notable, may not fully equip him to address the vast and complex challenges confronting Nigeria at the national level.

Orji Uzor Kalu governed Abia State from 1999 to 2007, running it more like a private business empire than a public institution. Under his leadership, the state suffered severe economic decline, infrastructural collapse, widespread poverty, and institutional rot.

Public services deteriorated, salaries went unpaid, and development stagnated, even as Kalu projected an image of prosperity based on political propaganda rather than real progress. After office, he was convicted of diverting billions of naira in public funds, sentenced to prison, and later released on technical grounds, not innocence.

Yet he continues to present himself as a national statesman and potential vice presidential candidate, ignoring a record defined by plunder, not governance. A man who so badly mismanaged one state should never be trusted with the leadership of an entire nation.

Nasir El-Rufai governed Kaduna State with authoritarian flair and a dangerous disregard for national cohesion. His tenure was marked not only by rising ethnic and religious violence, but by a cold, divisive rhetoric that deepened the crisis.

Southern Kaduna burned for years under his watch, while he issued inflammatory statements and dismissed victims. Rather than calming tensions, he stoked them. His idea of governance was domination, not dialogue.

His record on education and security, the two pillars he claimed to reform, was hollow at best and disastrous at worst. He ran the state like a battlefield, not a democracy.

Today, he parades himself as a reformer, but the legacy he leaves behind is one of bitterness, bloodshed, and institutional failure. El-Rufai’s presidential ambition is not built on unity or solutions. It is built on provocation and spin.

Godswill Akpabio ruled Akwa Ibom during Nigeria’s oil boom, a time when the state was flush with resources. Yet instead of translating that wealth into structural transformation, Akpabio spent lavishly on self-glorifying projects and political patronage. His tenure delivered glitter but no growth. Roads were built, but industries were not. Billions were spent, but few lives were lifted.

And today, as Senate President, he exemplifies the rot of Nigeria’s political class, presiding over a National Assembly that is bloated, wasteful, and disconnected from the suffering of ordinary Nigerians.

Under his watch, the Senate has become a theater of political favors, rubber-stamp legislation, and embarrassing excess. Akpabio’s ambition is loud, but his legacy is hollow. He has mastered the art of political survival while delivering little of value to the nation.

These are not leaders. They are political survivors. And survival is not the same as competence. Endurance is not capacity. Titles are not credentials.

This is the central failure of the Nigerian system: we mistake access to power for readiness to lead. Yet running a state in Nigeria is no real preparation for national leadership.

So if these positions are not qualifications, what should Nigerians demand instead?

What Voters Should Demand

Nigerians must stop electing men and women simply because they have “waited their turn.” They must start demanding true qualifications grounded in substance, not status.

1. A Proven Record of Solving Complex Problems

Leadership is not ceremonial. It is practical. Voters must ask: What has this person built, fixed, or transformed? What crises have they managed and solved?

2. A Vision Backed by a Detailed Plan

Aspirants must come with specific blueprints. Not vague manifestos. What will you do, how will you do it, how will you fund it, and who will help you?

3. National, Not Ethnic or Regional Thinking

Nigeria is too diverse to survive another tribal or sectional president. The country needs leaders who speak to every Nigerian, not just their region.

4. Crisis Management Experience

Nigeria is in perpetual emergency. We need leaders who have operated under pressure, made hard decisions, and shown competence in chaos.

5. Zero Tolerance for Corruption and Secrecy

Any candidate who cannot declare assets, account for past wealth, or walk free of scandal is disqualified. Leadership demands character, not performance.

6. A Competent, Credible Inner Circle

No one governs alone. Nigerians must examine who surrounds each candidate. If it’s the same discredited, recycled mediocrities — run and don’t look back.

7. The Courage to Break the System

Reform does not come from insiders protecting the status quo. Nigeria needs disruptors, people willing to tear down broken systems to rebuild the country.

The real qualification is not a title. It is transformation.

Until Nigerians demand these standards, the presidency will remain a prize for the powerful rather than a responsibility for the capable. As long as political recycling is mistaken for leadership, the country will continue its spiral of collapse and disappointment.

We must stop mistaking endurance in office for evidence of ability. Being in power is not the same as knowing how to lead. Having a title is not the same as having a plan. This country has been wrecked by men who rose to power without ever being forced to lead.

The presidency must not be a compensation package for those who have loitered around government for years. It must not be a retirement plan for failed governors, vice presidents, or senators.

We must demand more.

The future of 230 million Nigerians is too important to be entrusted once again to failed men clinging to empty titles.